Ag Fanacht (Waiting in the Irish language) is the exhibition of the project War Widows by Angelina Foster, funded by the Kildare Decade of Commemorations. Ag Fanacht is currently exhibiting in Athy Library, Co Kildare, Ireland and has been extended until the 4th of November 2023.

The women were always waiting, waiting for news of their loved ones, waiting for the pension, waiting for the vote, for equality. In July 2022, I travelled to France and visited 6 World War One cemeteries and the destroyed villages of Verdun. This work was created on reflection of the experiences, survival and cultural silence around Irish women and families of WW1 soldiers buried in Europe, the ones who never came home.

The Ireland that WWI soldiers left, from 1914 onward, was very different from the one their mothers, sisters, girlfriends and wives found themselves in by the end of the war. Many were left as single mothers with few supports and received little empathy or compassion for their terrible loss. Many of these women did not have a body to bury in Irish soil. Every community in Ireland has a burial ground, and the funeral has always had a huge role in Irish culture. But the families of soldiers buried in Europe never got to attend their loved ones’ funerals and their deaths were often not spoken of within their communities, so their stories were lost, and many grieving women were never able to visit the graves of those they mourned.

Wars tear families apart, but the deaths of Irish soldiers in World War One were different. As the war in Europe raged on, and the battle for Irish independence built up momentum, men made different choices about when and where to fight, and those choices built a wall of cultural silence for many families of Irish soldiers in post-war New Ireland, some felt shame or were seen as traitors for taking the King’s penny and supporting Ireland’s oppressor.

As our Decade of Commemoration comes to a close, our communities and national consciousness are processing empathic understandings of our past versus the impacts of colonialism imperialism and identity during this period and beyond.

AG FANACHT (WAITING) Exhibition Listing

- Ciúnas (Silence)

Medium: 3 colour Screenprint, edition of 7 VP

Price: Framed €300 unframed €150

For many decades the experiences of Irish soldiers who served in the Great War were unspoken of. A lot of records and correspondence were lost. During the Civil War, republicans had a strategy of intimidating anyone who had links with the crown forces. As the widows of British Soldiers, many women were shunned in their communities. Very few records exist of the experiences of women during WW1, the War of Independence, The Irish Civil War and beyond.

Life was hard for women, many women were more preoccupied with survival, and raising their children than equality. A culture of silence developed for soldiers who served in the British army and their families. They didn’t speak of their experience and women grieved in silence.

I have intentionally used the colour purple in the background, as the colour of equality. The 3 soldiers are my father’s uncles Martin and Michael and his cousin Jack. - Cumha – Grief 1

Medium: Natural ink drawings, derived from heather, Oak, poppy, dock seed, acorns with copper, iron, citric acid and soda ash.

Price: : €350 (framed)

She (the land) grieves for Her

Cumha is a series of natural plant-based ink drawings developed on reflection of the invisible overwhelming grief of families during and after WW1. I felt the process of creating botanical inks linked human grief with the land. There were many emotions I felt by visiting the World War 1 cemeteries and searching for stories of war widows and survivors. As the war raged on in Europe and momentum for Irish Independence grew at home, She (the Land) battled for survival under the weight of nations tearing her apart.

These circles are representative of pools of grief and cycles of life, whether through the effects of war, climate change or colonialism women and children are most affected. They also allude to cycles of violence, violence humanity inflicts on each other and the violence we inflict on the Earth. I was constantly reminded of events today and how the Earth has survived all these crises. Will we ever learn from history? - Cumha – Grief 2

Medium: Natural ink drawings, derived from heather, Oak, poppy, dock seed, acorns with copper, iron, citric acid and soda ash.

Price: : €300 (framed)

She grieves for Her.

There are so many connections to the land for women during this period and beyond. She is the Land, she (the land) is also wounded and torn apart in battlefields today as it was during WW1. She grieves for Him is also a reference to the Unknown soldier, loved ones whose bodies were never recovered and hence became the land. - Cumha – Grief 3

Medium: Natural ink drawings, derived from heather, Oak, poppy, dock seed, and acorns with copper, iron, citric acid and soda ash.

Price: : €300 (framed)

Grief 3 – illustrates Her hope, hopeful grief and the waiting. Many families could not accept the death of loved ones without a body to bury or mourn, some families featured photos in the Evening Herald asking soldiers returning to the front to send news of their husbands, sons, fathers, and brothers. Her hope is the Earth’s hopeful grief and waiting for the people she feeds to stop the hurt.

Cumha means grief in the Irish language. The use of Gaeilge is an important part of our identity and the establishment of our nation. For me, Gaeilge is linked to the land and our indigenous past. It predates colonisation and it has also fought for survival. - Fleury avant Douaumont

Medium: 2 colour screenprint, edition of 4

Price: €300 Framed, €150 unframed

Fleury avant Douaumont is one of the 9 ghost villages of Verdun I visited in 2022. I heard of these villages before going to France, although not part of the Irish story I felt a need to visit there. During the Battle of Verdun (Feb 1915 – Dec 1916) the Germans completely levelled to the ground and destroyed 9 villages:

Beaumont-en-Verdunois, Bezonvaux, Cumières-le-Mort-Homme, Douaumont, Fleury-devant-Douaumont, Haumont-près-Samogneux, Louvemont-Côte-du-Poivre, Ornes, and Vaux-devant-Damloup.

The villages that died for France was written on a plaque. The French people refused to erase the villages from maps lest we forget, there are street signs and markers where shops stood, many now covered in forest. It’s quite an eerie feeling walking around.

Looking up at the hills, you could imagine tanks & guns raining down, all I could think of was Ukraine today and where could the people go. Approx 3,000 Belgian refugees arrived in Ireland at the start of the war, and workhouses were used to house them, during 1918 the number of refugees in France reached 1.85 million. - Ag Fanacht (Waiting)

Medium: 4 colour screen-print, edition of 1

Price: €400 framed

I tried to imagine what it was like for families looking for news of their loved ones and found The War OfficeWeekly Casualty List, this one is 9 pages long. This particular front page announces the death of my cousin Jack Foster and Martin Foster injured. It is printed in the colours of the Irish suffragettes’ flag with Ag Fanacht in deep purple. Photographs showing the bodies of dead soldiers were not circulated during the conflict as they would discourage recruitment. Cameras were officially banned in 1915 on the Western Front. Similarly, this was originally a daily publication but was deemed too depressing. - Johnny I hardly knew ye.

Medium: 2 Colour screen-print in purple and gold gouache.

Price: €350

Johnny I hardly knew ye is a powerful anti-war song and one of the few war songs told from the perspective of a woman. It tells the story of an Irish woman who meets her former lover on the road to Athy, Co Kildare. After their illegitimate child was born, the lover ran away and became a soldier. He returns badly disfigured, losing his legs, his arms, yet at the end of the song she still keeps him. Several people mentioned this song to me. I’ve printed a rubbing of a World War One medal in the middle of the song. - Ag Fanacht

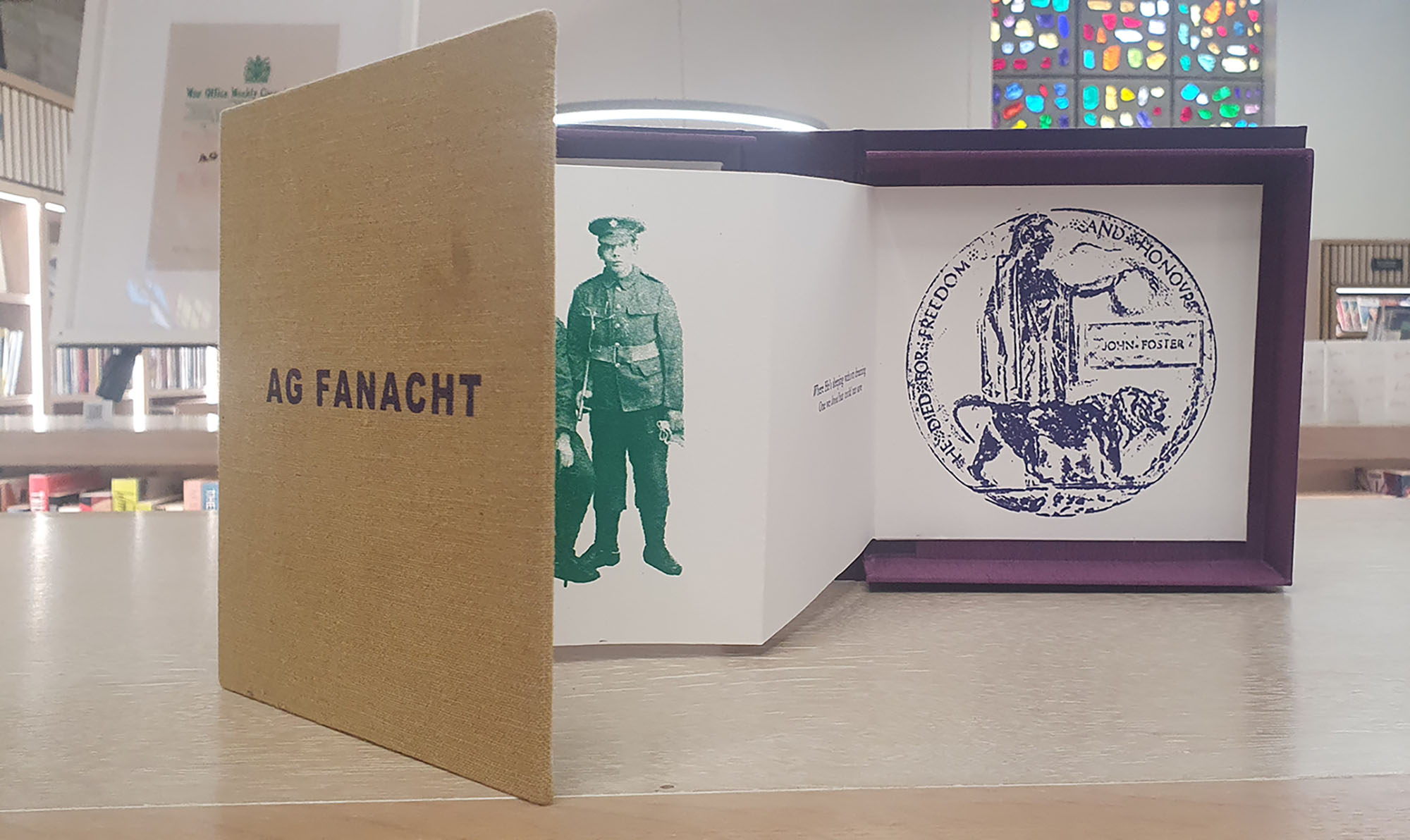

a. Limited edition of 3 concertina books, with 1 colour screenprint, bound in Irish linen cloth, naturally dyed with meadowsweet, printed by letterpress with Caslon typeface using blended purple & gold Hanco inks.

b. * 1 book inside a handmade purple clam box.

This box book is sealed secrets in a box, the poem was printed in the Nationalist on the 31st of August 1919 by my grandaunt Brigid Foster, on the first anniversary of her husband’s death in France. Purple is again used as the colour of equality, I wanted to include a box in the exhibition, with family secrets boxed away in attics throughout Ireland.

The 3 soldiers are my father’s uncles Martin and Michael and his cousin Jack who is buried in St Sever, Rouen. Like countless Irish families, their experiences in World War One were not talked about. Jack, Bridget’s son was born out of wedlock, as a result of which Bridget left the family home. Jack was raised as a brother to Bridget’s siblings. I discovered her story a few years ago, and finding connections to other women like her inspired me to learn more about women like her who ended up in workhouses, survived as widows or single parents, or encouraged their children to serve in the Great War for reasons including the need to secure income for their families. Bridget spent time in Athy workhouse, she married a soldier from Carlow called William Monks in 1916. William went back to France in 1917, died and was buried in Croisilles. I often reflected on how she found out about her son Jack. - Theatre of War

a. Limited edition of 3 concertina books, with 3-4 colour screenprints, bound in naturally dyed linen cloth, with flowers and leaves from the hawthorn tree, printed by letterpress with Caslon typeface using blended purple & gold hanco inks.

The language of War and language used in the media during this period caught my attention. The Theatre of War is a military term for an area where an armed conflict takes place, it almost seems like a mock war.

The use of the word imperial has also changed, once used with pride, now it is associated with oppression, racism and world poverty. This book recognises the 2 pioneering women, who were moved by McCrae’s poem and campaigned for the poppy to become an inter-allied symbol of remembrance.

In later times, in Ireland, Kenya, Malaysia, Argentina, Zimbabwe and many other nations where millions of lives were lost standing up against colonial power, the poppy became a symbol of British imperialism.

The poppy has become for many people, not a symbol of remembrance but a symbol of division.

9.7 million lives were lost during the Great War on both sides, with 3-4 million women widowed. Imagine the grief that echoed around the world with this colossal loss.

Imperialism and Poverty printed by letterpress on the back pages allude to the source and consequences of war. - Known Unto God

Concertina book, printed by letterpress on Awagami Shirakaba paper with Gill Sans Bold type, with the names of the soldiers commemorated at Thiepval. Names of 59 soldiers from Co Kildare, who never came home, with their next of kin written in ink made from poppies. The first cemetery I visited was Thiepval Memorial and Museum where 72, 205 men from British or South African armies who were declared missing in the Somme between July 1915 and March 1918 were commemorated. Imagine the number of lives impacted by this battle alone, the number of husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons who never came home.

The term Known unto God was penned by Rudyard Kipling, the famous British Nobel prize-winning writer. John Kipling was the only son of Rudyard and Carrie Kipling. He failed the medical for poor eyesight but his father used his connections and John went to war with the Irish Guards. John was reported missing in 1915, his body was never found in his parents’ lifetime and his name was inscribed on Menin Gate with countless other sons. His parents never came to terms with his death.

In 1992 Commonwealth War Graves Commission identified John Kipling’s body and a headstone with his name was erected.

I think I was most disturbed by these huge memorials to soldiers who were never found. The lists of names and regiments carved in stone and felt the need to write their names and families. The graveyards with row upon row of white headstones felt surprisingly peaceful, many with messages from families but places like Menin Gate and Thiepval did not for me.

Appendix & Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Kildare Decade of Commemorations Committee for their support, Kildare’s local history department, Karel Kiely and Mario Corrigan. The book written by Karel Kiely and Mario Corrigan “Remembrance: The World War I Dead of Co. Kildare” was a major source for information on this project. I would also like to thank Trudy Carmody who accompanied me on the trip to France, and my own mother, Tessie, for her support and for continually pointing out that women didn’t write down their worries, didn’t use the word trauma, they just got on with it.

Johnny I hardly Knew Ye (lyrics)

While goin’ the road to sweet Athy, hurroo, hurroo

While goin’ the road to sweet Athy, hurroo, hurroo

While goin’ the road to sweet Athy

A stick in me hand and a drop in me eye

A doleful damsel I heard cry,

Johnny I hardly knew ye.

With your drums and guns and drums and guns, hurroo, hurroo

With your drums and guns and drums and guns, hurroo, hurroo

With your drums and guns and drums and guns

The enemy nearly slew ye

Oh my darling dear, Ye look so queer

Johnny I hardly knew ye.

Where are your eyes that were so mild, hurroo, hurroo

Where are your eyes that were so mild, hurroo, hurroo

Where are your eyes that were so mild

When my heart you so beguiled

Why did ye run from me and the child

Oh Johnny, I hardly knew ye.

Where are your legs that used to run, hurroo, hurroo

Where are your legs that used to run, hurroo, hurroo

Where are your legs that used to run

When you went for to carry a gun

Indeed your dancing days are done

Oh Johnny, I hardly knew ye.

I’m happy for to see ye home, hurroo, hurroo

I’m happy for to see ye home, hurroo, hurroo

I’m happy for to see ye home

All from the island of Sulloon

So low in flesh, so high in bone

Oh Johnny I hardly knew ye.

Ye haven’t an arm, ye haven’t a leg, hurroo, hurroo

Ye haven’t an arm, ye haven’t a leg, hurroo, hurroo

Ye haven’t an arm, ye haven’t a leg

Ye’re an armless, boneless, chickenless egg

Ye’ll have to put with a bowl out to beg

Oh Johnny I hardly knew ye.

They’re rolling out the guns again, hurroo, hurroo

They’re rolling out the guns again, hurroo, hurroo

They’re rolling out the guns again

But they never will take our sons again

No they never will take our sons again

Johnny I’m swearing to ye.

Artist Statement- Angelina Foster – Blueway Art Studio

Launched in July 2022, Blueway Art Studio, my eco-socially engaged practice is based on collaboration with groups who have a shared interest in community, creativity and climate action. I have a keen interest in identifying activities and collaborators which focus on the voice of young people and women.

I am a member of Wom@rts, Limerick Printmakers and Mná· na nEalaín Collective, I have professional membership of Visual Arts Ireland and Into Kildare.

I have always had a huge interest in heritage and the role art, particularly print played in activism through the centuries. I host workshops which celebrate Irish women in print, and the impact of the letterpress on suffragism.

Sense of place influences on my practice locally are Mary Leadbetter and Kathleen Shackleton. Historical influences in terms of women activists in Ireland include Lilly and Lolly Yeats, Dun Emer and Cuala Press’ impact on the revival of indigenous Irish culture. While “tableaux vivants” touring the countryside with Maud Gonne, Alice Milligan and Inghinidhe na hÉireann was ahead of it’s time. Countess Markievicz, Eva Gore-Booth, Grace Gifford, Anna Sheehy-Sheffington. Contemporaries Pauline Bewick, Alice Maher and Aideen Barry have provided huge inspiration for many years.

In terms of artists in Europe during our period of Commemoration, the work and life of Käthe Kollwitz made a profound impression on me, particularly her woodcut “Parents” and sculpture “The Grieving Parents”. Natalia Goncharova’s “Mystical Images of War” was one of the earliest responses to the war in 1914.