The story of Shackleton in Antarctica tends to focus on the scale and bravery of the Endurance expedition, without noting the Kildare explorer’s printmaking and literary accomplishments.

My ‘Printmaking at the Sign of the Penguins’ project set out to explore the creative story of Shackleton in Antarctica and animate it for everyone who has an interest in the extraordinary ambition of Shackleton and his crew.

The recent discovery of his ship Endurance, lost in Antarctic waters for 107 years and his centenary year in 2022 have ignited interest in one of the greatest leaders of the golden age of exploration, and so it’s a great time to draw attention to Shackleton’s achievements as a writer, poet, and Antarctica’s first publisher.

The Printmaking at the Sign of the Penguins project – funded by Bank of Ireland Business to Arts Begin Together, in partnership with Shackleton Museum, Co Kildare – was designed to create awareness of Shackleton’s artistic achievements. It also explored how art can be created in challenging situations, shedding light on the printmaking and bookmaking practices undertaken by Shackleton in Antarctica, along with his crew.

The project’s name is a nod to the inscription on the first page of Shackleton’s book, and at the end of the project, I made a short film (see below) which was presented at the Virtually Shackleton event in 2021.

The Shackletons in Kildare

Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922), the world-renowned Antarctic explorer was born in Kilkea, Co Kildare. Whilst his leadership and survival skills are worshipped by many around the world, his deep roots in education and creativity, as well as his Kildare family influences, are often overlooked.

Shackleton’s family were residents of Ballitore, outside Athy, Co. Kildare, for hundreds of years, and they set up the first Quaker school there in 1728. His family always had a strong interest in the world beyond Kildare, and they were very creative people. His impressive grand-aunt Mary Shackleton Leadbetter was a writer, poet, suffragette, and abolitionist in the 18th century, and his sister Kathleen travelled around the Canadian Arctic in the 1920s painting portraits for the Hudson Bay Company. While today, we think of Shackleton only as an explorer, he was an impressive poet in his own right and a writer and editor for the National Geographic magazine in Edinburgh.

Printmaking in difficult conditions

Even at the planning phase for the expedition, Shackleton would have had to factor in the additional size and weight that the printing presses, type, and machinery contributed, and the fact that he decided to press on with bringing all of this equipment on the trip shows that this creative project was a big priority for him.

Shedding light on Shackleton’s printmaking process

In fact, the creative aspects of these expeditions counted for much more than killing time. They engaged and entertained the minds of the men in extreme isolation, but they also provided a powerful way of capturing and recording the expedition experience for posterity.

As a printmaker, I know how important it is to have ventilation and a clean, steady surface for drawing, plate registration, and printing. I became obsessed with trying to figure out how George might have worked with acids, how the salty water affected the printing and what happened to his printing plates!

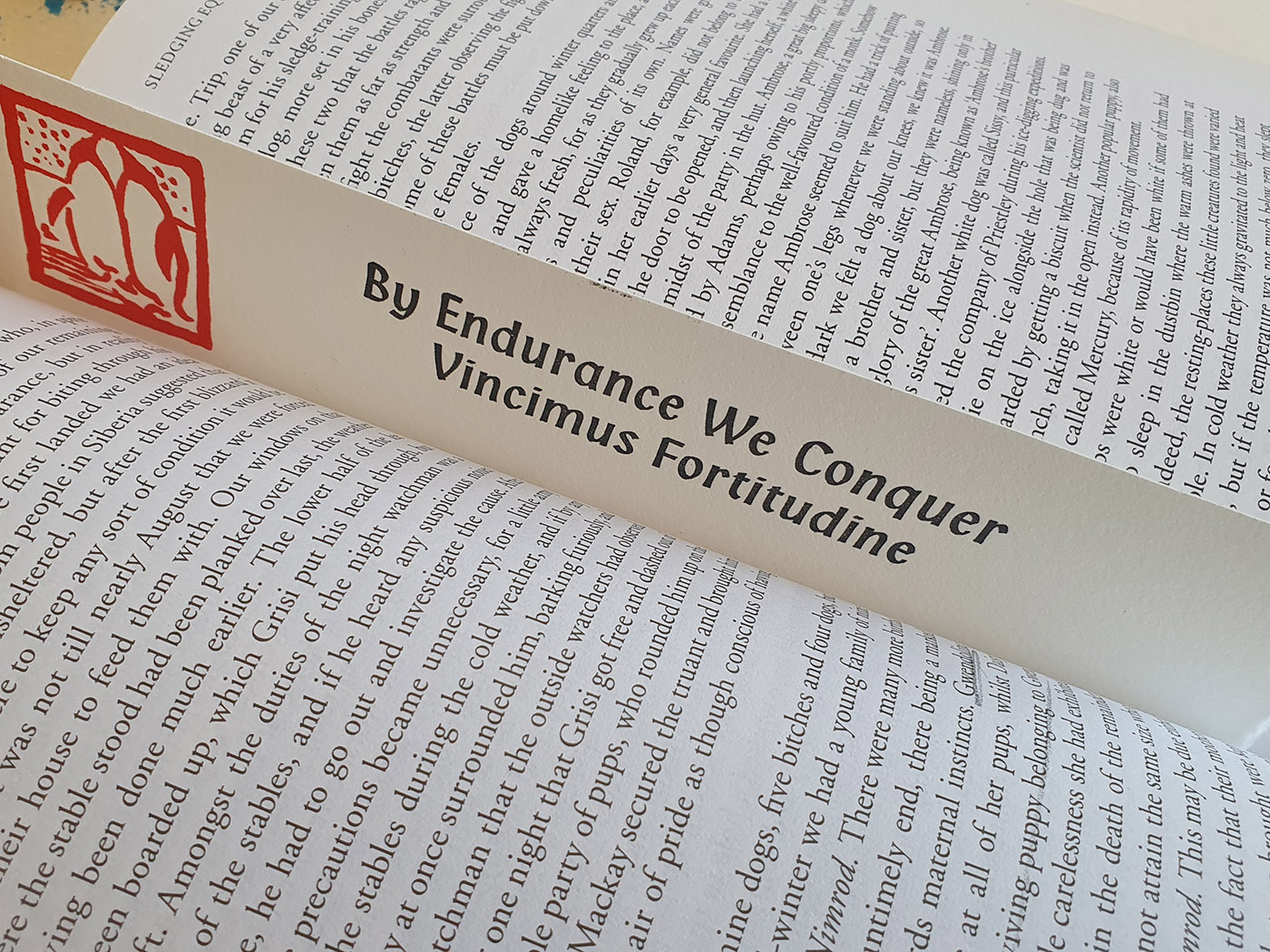

Margaret Walsh at Athy’s Shackleton Museum was incredibly helpful in helping me to learn about Shackleton and the expedition, and one of the museum’s directors, Seamus Taffe, kindly lent us his personal copy of Aurora for use in the film we made together.

As I worked on the film, Dublin’s Blackchurch Print Studio helped me to demonstrate stone lithography, allowing me to use some of their footage to help people gain an understanding of how Shackleton’s book had been produced and how that process had been affected by polar conditions. I also collaborated with Mary Plunkett of Ireland’s National Print Museum to demonstrate basic letterpress printing so we could show how Joyce and Wild would have set the type, as well as heated and inked the plates.

In his introduction to Aurora Australisand any references he made to the book, Shackleton always gave full credit to his crew, which has to be admired. Marston also clearly felt very fondly about the project, as he used the trademark of 2 penguins on his own book Antarctic Days.

Creating Art in Antarctica

In 1907, Shackleton decided to bring an etching press and an Albion letterpress with him as he travelled on a small whaling ship to the South Pole on the Nimrod expedition because he wanted to be the first person to write, print and bind a book in Antarctica.

This book “Aurora Australis” is now part of polar history and legend, but it was no small undertaking to prepare his crew for his book-making plans. His crew members, Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce received a 3-week crash course in typesetting, while the expedition artist George Marston had to learn to use aluminium plate lithography (algraphy) & etching. Marston was a watercolour artist before joining Shackleton and it was Ernest’s sister Helena who encouraged George to apply for the position of expedition artist and take on its printmaking duties.

As a printmaker, I have a particular personal interest in George and the challenges he faced, and I felt a connection with him as an art educator too. Marston worked as an art teacher in Bedales School – one of the first non-denominational co-education schools in England – when he returned from Antarctica, and he was also an influential director at the Rural Industries Bureau until his death in 1940.

On the expedition, Marston printed using lithography, etching, and drypoint. Aluminium plate lithography was a relatively new process at this time, and so the team were pushing boundaries artistically as well as geographically. The expedition mechanic, Bernard Day, bound the book, even though he had no known previous experience as a bookbinder!

Incidentally, Sir Joseph Causton & Sons, the company that donated Shackleton’s print equipment and paper and trained the crew produced propaganda and rallying posters for World War One, as well as labels for Guinness.

I am very grateful for the time many of these people afforded me to support my research and my subsequent Shackleton-focused projects.

Fresh avenues to explore

The award of funding from Begin Together afforded me the time to research Shackleton’s printmaking and and immerse myself in the processes fully so I could demonstrate and share them with people interested in Irish and polar history, as well as the history of printmaking.

The project went on to inspire and shape some of the creative workshops I host for the public at my studio in Ireland’s Ancient East; my work with schools, including the primary school in Shackleton’s Kildare birthplace; and festival events, including Cruinniú na nÓg. It has also become the basis for further collaboration with the Shackleton Museum and the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust.

I am already planning future projects that focus on Shackleton’s adventures travelling the world to give lectures on his expeditions, as a member of The Explorers Club, and I would love to do more to explore the stories of the Shackleton women too.

Project: Printmaking at the Sign of the Penguins

Funders: Bank of Ireland Business to Arts Begin Together Arts Fund

Partners: Shackleton Museum, Co Kildare

Collaborators: The National Print Museum

Outputs: I created a short film – Printmaking at the Sign of the Penguins (above).